On the brisk fall morning of Oct. 22, 2016, roughly 200 people congregated at Lions Municipal Golf Course. They were gathered to see their beloved golf course, “Muny,” named to the National Register of Historic Places, and honored as the first golf course south of the Mason-Dixon line to desegregate.

The crowd slowly filled the white chairs arranged in rows on the first tee box. Austin Mayor Steve Adler wore a black suit and purple shirt, which complemented the purple worn by the Lions Club members who were seated at the front. The African-American men’s chorus from the Ebenezer Missionary Baptist Church was seated to the side in white dress shirts and black pants. And General Marshall, one of the “Legends of Lions,” even wore a Dak Prescott Cowboys jersey.

Muny is the quintessential public golf course. Although it is located in one of Austin’s most valuable neighborhoods, players can wear concert T-shirts and denim cutoffs. The old electric carts rattle along cracked paths. And, the range balls do, in fact, range. There are old Maxflis with dimples smoothed by age, balata Titleists with smiles cut by mistimed irons and, occasionally, the perfect Pro-V1. Those often end up in play. Your golfing pedigree does not matter. The only requirement is that you pay the $24 green fee.

A nearby pianist played a ragtime tune as the crowd found their seats. At the front of the congregation, a green cloth was draped over a plaque waiting to be unveiled. As the ceremony proceeded, some neighborhood residents stood with their leashed dogs on the putting green, an act that would set off greens keepers at most other traditional courses.

Muny’s future and role in Austin has been the subject of debate since 1973. The city, which runs the course, leases land from the University of Texas System called the Brackenridge Tract. The lease is set to run out in 2019, at which time Muny could be forced to close in order for the UT System to develop its land in a financially lucrative manner. Events like the ceremony have become a staple for the Save Muny movement’s efforts to save the course.

Save Muny activist Steve Wiener welcomed the crowd on behalf of the group, and other supporters of the cause took their turns speaking.

“When and if our city loses a place like this, it never comes back,” Adler said.

Austin City Councilwoman Sheri Gallo spoke about her personal motivations for saving the course. She joked that if she did not attempt to save Muny, her husband would change the locks on their home.

Congressman Lloyd Doggett spoke on behalf of the non-golfers who hope to see the course saved. Muny represents “so much of what makes Austin, Austin.”

“It has meant so much to so many people,” added lifelong Austin resident and two-time Masters champion Ben Crenshaw. “A lot of people have tried to put monetary values on this place. You can’t take away people’s hearts.”

Gallo proclaimed on behalf of the city that the date be recognized as “Save Muny Day.” The declaration got a roar out of the crowd.

Volma Overton Jr., one of the prominent African-American figures in Muny’s history, encouraged the crowd to join him in “Hands Around Lions.” Members of the crowd gathered around the iconic lion statute on the putting green and held hands for a photo.

A chant began.

“Save Muny! Save Muny!”

Among this diverse group of people lingered a man who stood out more than the rest. He looked to be nearing 30 in age, sunglasses resting on the brim of his sun damaged golf hat. But his belt buckle is what caught the eye. It said one word: “Hope.”

Indeed, it was hope that brought everyone together on that fall day. Hope to preserve the golf course that means so much to so many.

—————————————————————————————-

Muny sits on land originally deeded to the University of Texas in 1910 by Col. George Brackenridge, a member of the Board of Regents. He hoped the university would move its main campus to the banks of Lake Austin. Although his dreams of relocating the campus were never realized, the Brackenridge Tract has been owned by the university system ever since.

In 1924, members of the local Lions Club decided they wanted to build a golf course. They partnered with the City of Austin to establish the Austin Municipal Golf and Amusement Association, and worked out a deal with the University of Texas System Board of Regents to lease land on the Brackenridge Tract. A modest nine-hole course was erected by the end of the year, and Muny was born. By 1937, the Lions Club built a clubhouse and expanded the course to 18 holes, at which time they donated the course to the city.

Beginning in 1972, the UT System Board of Regents began toying with the idea of closing Muny in order to develop the land. After all, the Brackenridge Tract is a valuable property, and precious asset for UT. Eventually, the city was able to work out a deal with the board putting off plans of development until 1987.

But two years before the expiration of the lease, there were more rumblings from the university that they hoped develop the land. At that time, the land was rapidly increasing in value. When it was gifted by Brackenridge, the land was on the edge of town, however, with the rapid growth Austin was seeing, the location near downtown was highly desirable.

In 1987, a two-year lease was agreed upon, and then, in 1989, a deal was struck extending the lease for an additional 30 years, until 2019. The lease called for the city to pay $200,000 per year, with an increase of 5 percent every five years for the duration of the lease. Currently, the annual rent for the 141-acre property is hovering near $500,000, only a fraction of its valued worth.

According to The Brackenridge Tract Task Force Report from 2007: “the Board of Regents has a legal and ethical obligation – in point of fact, a fiduciary duty – to carry out Colonel Brackenridge’s fundamental philanthropic purpose and mandate when the gift was made: to use the tract for the benefit of the educational mission of the University.”

The Save Muny movement was born because the course would become a victim of circumstance if ideas like these came to fruition. The group was founded by Patricia Bedinger and Pete Acosta in 1972, and composed mainly of members of the city’s golf advisory board and residents of the Tarrytown neighborhood. The group is now led by Peter Barbour, and is made up of “interested citizens,” according to Mary Arnold, one of the leaders of the cause. Save Muny made it their mission to spread awareness about their fight, and the history behind the course. If you drive around Tarrytown, you are sure to see Save Muny yard signs in front of homes of the sympathetic residents populating the area.

However, good news came for Save Muny recently. In a letter dated Jan. 17, 2017, UT President Greg Fenves indicated the university would be open to discussing a possible lease extension.

“I write now to ask if the City has any desire to negotiate an extension or renewal of the Muny lease on terms closer to current market value past the initial term,” Fenves said.

There has been little news from either party since the publication of the letter, but Fenves requested the city give him a response to his inquiry by March 1.

—————————————————————————————-

Five men stood on the first tee box waiting to tee off in a skins game on another busy Saturday morning at Muny. They were an eclectic group of golfers, with older age being one of their few similar characteristics.

Eddie Castillo, the man who started the skins game in 1985, sported a gray mustache and wore a black pullover. David Aldrich, a tall, gangly man, dressed in a pink shirt and black jeans. Next to him was Marshall Hinton, in a white golf polo and a pair of plain blue jeans. Cary Petri sat in the cart looking patriotic in his red vest, white shirt and blue slacks.

The last of member the group was the most striking of the bunch. David Harrell wore a plain white T-shirt with the phrase “Mr. Muny says ‘Save Muny 4Ever’” brandished across the front. He teed off from a tee box ahead of the other gentleman, but his place in the group could not be mistaken. “Mr. Muny” began playing the course in 1951 and estimates he has played around 10,000 rounds there. He may know the course better than anyone.

“People used to call me on the phone and tell me where their ball was,” he said. “And I could tell them what it would do on the greens.”

He would come out to the course nearly every day when he was younger, after he finished his job of painting houses. Eventually, one of the course regulars gave him the nickname, and it has stuck ever since.

The men in the fivesome have made the weekly game a habit for the past 31 years. If you visit Muny on a Saturday morning, you’ll almost certainly find them playing.

“We’re just a bunch of old guys who love golf and love the course,” Aldrich said.

The level of expertise of Muny the men displayed, particularly on the grainy greens, was striking. The trick, Harrell explained, is that the grain always goes towards the setting sun.

The men have been playing the course for so long that the layout of Muny has started to feel longer than the 6,000 yards the scorecard shows.

“I used to hit driver, 5-iron into this green,” Harrell said about the 500-yard par-5 12th hole. “Now, I hit driver, 5-iron, 5-iron. That extra 5-iron shows that I’m getting old.”

These five men are only a fraction of the skins game. Petri said that every Saturday there are about 25 people who play. Each week he sends out a mass text message to roughly 100 people inviting them to join, and the 25 who come out every week are always a diverse bunch.

“We’ve had everyone from lawyers, doctors, attorneys, all the way down to people just scraping by,” Aldrich said. “Anyone is welcome in our group.”

—————————————————————————————-

Beat up tee boxes and slow greens are par for the course, but that only adds to the charm of it.

Muny is nestled in the affluent Tarrytown neighborhood of West Austin. The entrance on Enfield Road winds through a grove of cedar trees before coming to a clearing that reveals the brick clubhouse and small putting green. At the center of the green sits a statue of a lion.

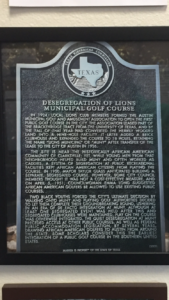

The course is located a short walk from the Clarksville neighborhood, a historically African-American community. Men from the neighborhood assisted in building the course, and many of them were employed there as caddies in its early days. However, laws keeping public facilities segregated prohibited them from playing the course.

That all changed in 1951. There were suggestions to build a separate course for African-American members of the community earlier in the year, but it was not cost-efficient and the idea was scrapped. Eventually, the course was peacefully integrated. One day, two young black caddies — Alvin Propps and another caddie, whose name was not documented — simply walked onto the course and began playing, forcing the hand of city officials. They were allowed to finish their round. Emma Long, a white city council member, was quoted as saying, “Just let them play.” This historic civil rights milestone is the event that Save Muny has hung its hat on in favor of keeping the course open.

From then on, black golfers were accepted at Muny, and the news soon spread across the state. African-Americans from all over Texas ventured to play there, as it was the first golf course in the South to desegregate. Even former heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis made an appearance in 1953. Four years after Muny’s peaceful integration, the Supreme Court decided to force integration of public golf courses in their decision of Holmes v. City of Atlanta.

However, bleaker days were on the horizon for Muny.

—————————————————————————————-

Save Muny has dedicated holes at the course to the people that have come to define it. In the Saturday skins game, there are two such Legends of Lions. Petri is one. He and his brother, Randy, have the 12th hole named after them. They grew up in a house just across the road from the driving range, and continue to play Muny over half a century after they began making memories there.

Harrell is the other legend in the group. His hole is the par-3 13th. He said he hopes to record his 13th career hole-in-one on it someday.

Although the 13th didn’t produce any timely theatrics on that day, Harrell was still eager to share any and every story he had about Muny. Such as how he attended O. Henry Middle School just across the road from the eighth hole, or how he would “park” with his high school girlfriends on the road next to the ninth green. He explained that Ben Hogan is his hero. One year on Hogan’s birthday, he made a birdie on the 16th hole, known as the “Hogan Hole.” So naturally, he stopped to sing “Happy Birthday” to the deceased golf legend.

To these men, Muny is not just a golf course, but rather a refuge from life’s difficulties. Aldrich said no matter what happens during the week, he can look forward to getting to play in this game. Harrell revealed that his live-in ex-wife passed away earlier in the week.

“Coming here helps me get my mind off of it,” he said.

If something were to happen to the course, the weekly skins game would still go on. Even now, it is scheduled at other area courses when events at Muny interfere with their tradition. But it would lose something if the course were to leave.

“We’ve got a lot of history out here,” Petri said. “That’s why you can’t let this thing go.”

—————————————————————————————-

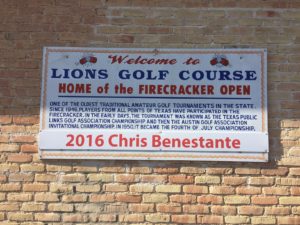

Starting in 1946, Muny was the site of the Firecracker Open, an annual event that brings amateur golfers from all over the region to Austin. The tournament is the oldest amateur golf tournament in the state. In its infancy, it was known as the Texas Public Links Golf Association championship, with several other name changes coming over the years. But in 1967, following a short stint being hosted at nearby Morris Williams Golf Course, the tournament returned to Muny and was renamed the Firecracker Open.

The tournament has a special place in the history and character of Muny. A win at the Firecracker is an honor that only a handful of people can claim. Billy Clagett, yet another Legend of Lions, holds the record winning the tournament six times.

“I didn’t think it was that big a deal,” he said of his first victory. “And then I kept winning the darn thing. Now I can look back on it and say, ‘Man, this is pretty hard to do!’”

There have been several memorable editions of the tournament over the years. Before he ever slipped on the green jacket amid the pines and azaleas of Augusta National, Crenshaw polished his winning ways on his way to the 1969 Firecracker title. The year prior, fellow World Golf Hall of Famer Tom Kite took the crown. Between 1990 and 1995, the tournament was dominated by Clagett, as his name was carved into the Serta Trophy in five of six years. In 2007, Brenden Redfern became the youngest winner ever at the age of 14. And this past summer, Chris Benestante won his first Firecracker just months after being released from drug and alcohol rehab, including a historic 27 during his second round back nine.

“Lions is such a great place,” Benestante said. “It’s historic, I mean, it’s Muny.”

But Muny hasn’t just been a playground for amateur golfers and aspiring pros. In 1950, golf legend Ben Hogan played there in an exhibition alongside long-time Austin Country Club golf professional Harvey Penick. The event was regarded as the biggest golfing spectacle in Austin prior to the WGC-Dell Technologies Match Play coming to town in 2016.

The connection that Kite and Crenshaw have to the course is deep-rooted as well. Prior to donning burnt orange together in their collegiate victories, they honed their skills at Muny as kids. Crenshaw even purchased his trusty Wilson 8802 putter in the pro shop; the same putter he would ride to his 1984 and 1995 Masters triumphs.

However, the battle over the fate of Muny has left the former Texas Longhorn teammates divided. Crenshaw has been adamant that the course needs to be preserved, while Kite hasn’t been as sympathetic. In 2008, Kite was strongly in favor of building a new golf course on site. It was to be designed by his golf course design firm, although he insisted that was not a motivating factor. The ambitious plan did not end up taking hold, but the dilemma illustrated Kite’s stance on the matter.

“The bottom line for me, I just can’t see this place being developed,” Crenshaw said. “I don’t have any hatred for UT, or anything like that. I just think it’s too precious of an asset, and it just simply means too much to people.”

—————————————————————————————-

At the conclusion of the ceremony, attendees were encouraged to gather in the clubhouse for a reception. Arnold, Marshall and the other faces of Save Muny posed for pictures in front of the lion statue, and three young junior golfers began rolling putts on the putting green as the cleanup commenced. Other members of the crowd embraced one another and stowed the moments of the event in their memories, because there is no guarantee on how many of these moments at Muny they have left.

Although the fate of the course is not yet decided, anything beyond May 2019 is uncertain. That is why events like these are so crucial. Having prominent community figures like Adler and Crenshaw pleading on behalf of Save Muny is invaluable to its cause. And even if the worst-case scenario becomes a reality, Muny will live on in the memories of those it touched.